In calculus class you learned that imaginary numbers are real. They are used to find the square root of negative numbers. Of course, those same mathematicians say it is infinity to any specific point on a line. Well in the accounting world, imaginary numbers are used on the income statement to account for depreciation expense. Those same imaginary numbers are then used on the balance sheet as accumulated depreciation.

Scenario one: A business owner borrows his working capital from financial institutions. Scenario two: A business owner self-finances. Before I go any farther, let me remind you, life is not fair. Everyone has their own special advantages. Your competitor will use his advantages to his benefit, you have to do the same. Some people’s advantage is simply, they are willing to work harder. Money is a big advantage in the business world. People that are able to self-finance have an advantage over those who have to borrow.

In scenario one, Larry Leverage, financed all of his hay equipment from John Deere Credit. His annually note is $60,000. In scenario two, Richie Wells, purchased all of his hay equipment outright. Both men started their perspective hay businesses with all new equipment worth $400,000.

Larry leases a ranch with 100 acres of prime hay fields. Richie owns 300 acres of prime hay fields.

Both men have expenses they pay out of their business checking account. These expenses are real expenses because the cash is coming out of their bank accounts. Both men sell their hay to offset their expenses, hopefully leaving a profit. Both men own barns suitable for maintenance, equipment and hay storage. Both men pay $3,000 a year for insurance. I am considering the barn as real property that will increase in value, thus no depreciation expense.

Here are the differences in the two men’s operations. Larry pays $4,000 a year lease on his hay field, while Richie pays $400 a year taxes on his hay field. Larry pays $60,000 a year to John Deere Credit, while Richie does not. Larry produces and sells 7,200 square bales a year, while Richie produces and sells 21,600 square bales a year. As we all know, there are a lot of variables that come into play to determine hay production yields. Some of these variables are rain, fertilizer, soil, sun, temperature, herbicide, and variety of grass. Timing of these variables also plays an important role in production. I suspect there are other variables as well. For this example, let’s assume both Larry and Richie have the same variable conditions. The only real difference is Richie’s operation is three times larger. Economies of Scale, can definitely be an advantage.

All business should look at their Economy of Scale. What is the maximum yield (production) per the most economical gain? In the hay business, the best way to increase yield is to apply more fertilizer and water. It is simple to see the large investment in pumping water is not worth the expense. Some hay producers do irrigate so maybe it does make economic sense. Irrigation does guarantee a hay crop every year. Most hay producers rely on rain. Irrigation is a nice option for those able to self-subsidize their operation.

A better analysis of Economy of Sale is fertilizer application rates. At some point, the economic gain declines. In your analysis, track your cost enough to know your minimum Cost of Goods Sold. Fertilizer is a large input cost that effects your COGS. In my operation, 200 pounds per acre cost $48 per acre. With average rain my yield is 45 small square bales per acre. My total fertilizer COGS is $1 per bale. My total (all inputs) COGS is $5 per bale. At 400 pounds per acre, my fertilizer input cost doubled, but my yield only increased by 20%. My total fertilizer COGS is $1.67 per bale. My total (all inputs) COGS is $5.80 per bale. My selling price per bale is $8.00, so my greatest profit is when my COGS is the lowest.

The second analysis of Economy of Scale, is focused on Fixed Costs. The depreciation expense of fixed assets are fixed costs. Other fixed costs include taxes and insurance.

Useful life is based on many variables such as, environment, storage, machine hours, and technology. Useful life is extended when equipment is taken care of, like regular maintenance and stored inside a barn, as opposed to those who park their equipment in the hot sun or at the salty beach. Some use their equipment 300 hours per year while others use their equipment 2,000 hours per year. With useful life, machine hours are more important than years of age. Also, newer equipment is much more user friendly due to technology. Outdated equipment does not have much useful life value.

When you lease a piece of equipment, you are pay for the depreciation expense, plus profit. The lease companies base their lease rate on machine hours. They know the useful life of their equipment and set the lease rate accordingly. Equipment leasing companies maintain newer equipment than the average rancher. These lease companies sell off their returned equipment while the equipment still has low machine hours and a high residual (salvage) value. Annual lease rates will be higher than annual depreciation expense. The annual lease payment is a real expense while the annual depreciation expense is an imaginary number. Because of the new lease rules implemented by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), there are no longer any tax advantages to leasing nor ability to hide the liability, of the asset, by leasing as opposed to purchasing.

Unlike the federal income tax graduated scale, which increases as income increases, the depreciation expense scale, deceases as machine hour’s increase. In other words, new equipment decreases in value faster than older equipment. New equipment decreases in value with every additional machine hour. That value decreases with time. Annual depreciation expense is higher for businesses that trade equipment every two years verses business that trade every ten years. Many businesses work their equipment hard and put lot of machine hours on their equipment every year. Those businesses need to trade equipment often.

Another way to look at this is, if you purchase all new equipment, worth $400,000 for your hay business, the depreciation expense, per year, depends on how much you use that equipment. For tax purposes that equipment is depreciated per whatever schedule you pick, usually an accelerated schedule to maximize your annually deduction. For true costs/revenue matching purposes, your equipment should be depreciated based on machine hours. If you experience a dry year and don’t bale any hay, thus no machine hours are put on the equipment, than no depreciation expense should be recorded that year. The next year may bring plenty of rain, spaced out at perfect times, thus 500 machine hours may be logged on all of the hay equipment. Most hay equipment, that is well maintained, should have a useful life of 10,000 machine hours. 500 machine hours would be a depreciation expense of 5% of $400,000 or $20,000 per year.

The $20,000 depreciation expense may not seem like a real expense, because money is not coming out of the checking account. Larry, who has an annual note to John Deere Credit for $60,000 may think he is entitled to that much depreciation expense each year. That is not the case. Paying a liability has nothing to do with a depreciation expense. Costs records are for the ranchers benefit to analyze his business’s financials. The rancher needs to make sure he recognizes his annual depreciation expense, even though it does not involve writing a check.

Back to our example with Larry and Richie. Larry has an annual equipment note, land lease, and equipment insurance costs of $67,000. Richie has an annual equipment insurance and property tax costs of $3,400. Larry produces 7,200 square bales one year and Richie produces 21,600 square bales that same year. Larry’s annual cost per bale is $9.31. Richie’s annual cost per bale is $0.16. In addition, both men have the same variable cost per bale of $3.25. The problem with this comparison is, it’s not accurate. The comparison should be based on annual fixed overhead, not annual costs. Larry’s annual equipment note to John Deere Credit is not fixed overhead. Both men have depreciation expense that is not accounted for. Depreciation expense is part of the fixed overhead.

Let’s recalculate based on annual fixed overhead in lieu of annual cost. For Larry to produce 7,200 square bales each year, he will put 250 machine hours on his hay equipment. For Richie to produce 21,600 square bales each year, he will put 750 machine hours on his equipment. Larry’s depreciation expense is $10,000 while Richie’s depreciation expense is $30,000. Larry’s actual fixed overhead expense is the $10,000 depreciation expense, plus $4,000 land lease expense, plus $3,000 equipment insurance expense for a total of $17,000 or $2.36 per bale. Richie’s actual fixed overhead expense is the $30,000 depreciation expense, plus $400 property tax expense, plus $3,000 equipment insurance expense for a total of $33,400 or $1.55 per bale.

The hay business, like many other businesses, is seasonal. Some regions may have only one cutting per year and other regions may have two or three cuttings per year. Either way, the window of opportunity is limited. For Richie to put 750 machine hours on his hay equipment in one year, to bale his 21,600 square bales, he would have to work 15 weeks that season. As both Larry and Richie live in a region that only gets two cuttings a year, working 15 weeks a season is not practical. Richie has several options, more equipment, larger equipment, or bring in contract help. Either way, Richie must spend twice as much money, as Larry, on equipment. Richie decides to double his equipment investment, giving him twice as much equipment. Remember now, Richie has three times the yield. That is economy of scale.

Because Richie now has twice as much equipment, Richie’s machine hour’s decreases from 750 MH per year to half of that, or 375 machine hours. In this new scenario, Richie’s actual fixed overhead expense increases to $30,000 depreciation expense, plus $400 tax expense, plus $6,000 equipment insurance expense for a total of $36,400 or $1.69 per bale. Remember, the depreciation expense is an imaginary number, based on machine hours used per year, divided by the total useful life machine hours. In both of Richie’s cases, his depreciation expense stayed the same at $30,000 per year. In Richie’s case one, his per bale costs came out to $1.55, but that was not practical from a timing point of view. Richie’s case one computed at 750 MH / 10,000 MH, or 7.5%. Then multiply the 7.5% by the total investment of $400,000. That comes to $30,000 for depreciation expense. I am assuming no salvage value. In case two, the machine hours was cut in half due to the doubling of equipment, so that computed at 375 MH / 10,000 MH, or 3.75%. Then multiply the 3.75% by the total investment of $800,000. (Remember, the equipment investment was doubled.) That comes to the same $30,000 for depreciation expense. Once again, I am assuming no salvage value. Believe me, after 10,000 MH and years of work, the resale value is extremely small.

Depreciation expense is real in the sense the equipment decreases in value with every machine hour. The reason I refer to depreciation expense as an imaginary number is because no real money is credited (removed) from your bank account. A prudent business man would divert depreciation expense, real money, to a savings account. For every debit to depreciation expense and credit to accumulated depreciation there should be a debit to savings and credit to checking. In some sense, that is what Larry Leverage is doing. By financing his equipment, Larry does have real money he is forced to pay every year. Even though a liability payment is not the same thing as a depreciation expense, it can serve the same purpose. Larry knows he has to make enough money every year to cover his $60,000 annual note. You can bet, Larry prices his hay to cover his annual note ($60,000 / 7,200 square bales = $8.33 each) plus his variable cost of $3.25 per square bale for a total of $11.58 per bale. Larry will not be competitive at this price so he is forced to keep all of his hay for his own use. The plus side on this is an increased feed cost to offset ordinary income on his cattle operation.

Richie, on the other hand, prices his hay to cover his annual depreciation expense plus other fixed cost ($36,400 / 21,600 square bales = $1.69 each) plus his variable cost of $3.25 per square bale for a total of $4.94 per bale. Richie knows the market will bear $8.00, leaving him a profit of $3.06 per bale. Richie is in a financial position to either sell some or all of his hay to hay customers, or feed some or all of his hay to his own cattle.

In summary, liability payments are easy to remember when calculating price, but for those who pay cash and do not finance, make sure to include the imaginary number of depreciation expense when calculating your selling price.

Brett Bickham

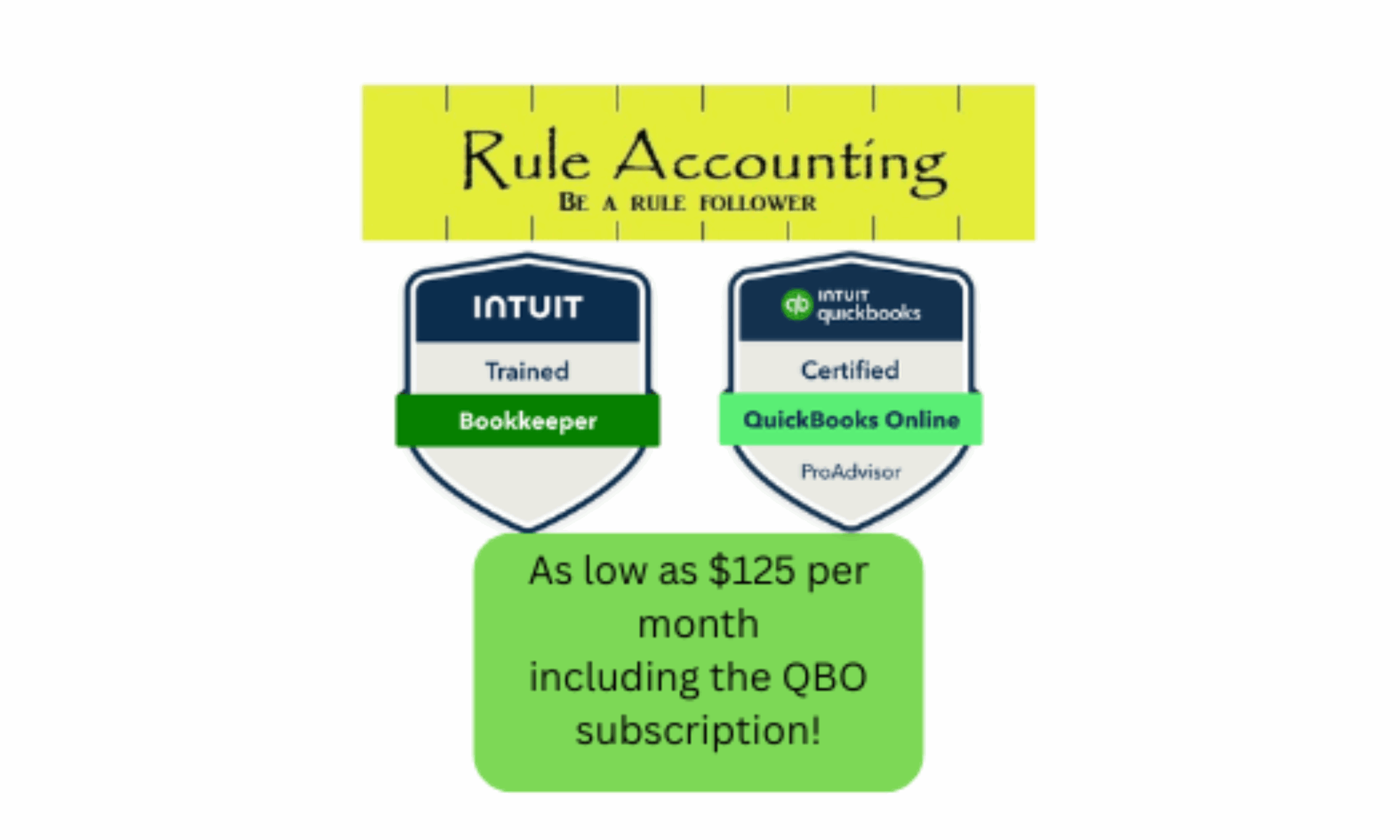

Rule Accounting, Bickham Ranch

Clifton, TX Aug. 26, 2020